The Middle Ages

The boss of the my boss is my boss

Like today, some people lived better than others in the Middle Ages. In fact, very few had a better life than the rest of them. It was all based on wealth (like today). But unlike today, when basically everybody could get rich with proper attitude, tools, and luck, in the Middle Ages, one should have been born into a wealthy family. Access to power and money was limited to a few people. The social hierarchy of the Middle Ages was very different from our contemporary hierarchy and was based on the amount of land someone owned.

Here is the simplified social tree:

The King

He was the head of the state, the boss of everybody else, had the most power, and was the richest of them all. His mom and dad were usually kings and queens, too, and the same was true about Grandpa and Grandma.

Some kings were better than others, and a few of them declared themselves Emperors, which is a bigger, fatter king who ruled over more than one nation.

The king was the boss of the barons, the lords, and the peasants. Sometimes, in some places, they were the boss of the bishops, too.

The Bishops

These people were chosen from within the church. They were once priests but advanced to administrative positions. It looks like they are mainly remembered as tax collectors, which, like today, nobody likes. They ruled over dioceses and were the bosses of all the priests and monasteries within a diocese. They were very rich, and often, they grew powerful and influential.

The Barons

Barons were people who received a tenure, or fief, from their boss, the King. At first, they were knights, and the King gave them a piece of land as a reward for their bravery in a battle. Then, they ruled over that piece of land, acquiring all the agricultural products, selling them, and making money. If one was raised to the noble rank of baron, then their children would be barons, too.

Over the centuries, some barons grew so powerful that they didn’t want to work for the kings anymore and made their own state so they could, too, be bosses.

The Lords

The Lords were people who rented land from the barons (who were given land by the king). So, barons were the lords’ bosses. A baron could be the boss of many lords.

The lords had the peasants work the land for them. They were not as rich as the barons, and many of them lived a simple life, but they had a better social status than the peasants. And they could advance to be barons if they did well in battles and killed a lot of enemies.

The peasants

The peasants were the lower people in the European Middle Ages hierarchy. They made up the majority of people. They lived a simple life, and they worked hard for their bosses, who were the lords. In exchange for their hard work, they usually got bread and beer. They had a very small piece of land that the lord had given them so they could have some other food besides bread and beer. The son of a peasant was a peasant, too, and there was no chance that such a son would, someday, advance to a lord position.

So, between or within these social classes, there were other positions held by people chosen within that respective class. These positions were mainly administrative jobs with little or no influence over the system.

Historians have a name for this European Middle Age Hierarchy: it is the cold Feudal System Or Feudalism, where a feud is a piece of land given to somebody in exchange for some sort of service. The Feudalism system of the Middle Ages is, though, more complex, and I may describe it in other articles.

Wednesday, August 17, 2011

Wednesday, June 29, 2011

Medicine in the Middle Ages| A list of healing herbs

How did the people of medieval Europe live without health insurance, hospitals, clinics, and other forms of health care that are available to us today?

Well, most people suffered in silence; some may haven't even known they were sick, as many diseases were diagnosed later. Or if they knew, it was more likely an acute pain that they could not take it anymore.

The most common form of treatment was the medicine administered to them by doctors (who had studied some classic Greek and Roman medicines) or, in small and remote communities, by other healers. There were physicians, barbers, surgeons, itinerary surgeons (traveling from place to place and offering their services to the wounded), healers (people without any formal training but a lot of hands-on experience in working with medicines), and apothecaries (the pharmacists of today).

The majority of medicines available in the Middle Ages were obtained from plants, herbs, and spices that were simmered, boiled, minced, and mixed with other ingredients to make a medicine that was mainly drunk, eaten, and occasionally inhaled.

Here is a list of herbs, spices, and other plants used in curing (see Daily life in the Middle Ages by Paul B. Newman, p 261):

|

| Hippocrates, greek physician, (cca 460 - 370 BCE) |

Rosemary

sage

marjoram

mint

dill

squill

pimpinella

henbane

betony

pennyroyal

cumin

cardamon

ginger

cloves

rhubarb

lettuce

and seeds of various trees

sage

marjoram

mint

dill

squill

pimpinella

henbane

betony

pennyroyal

cumin

cardamon

ginger

cloves

rhubarb

lettuce

and seeds of various trees

Other healing solutions included some unusual matters like pig dung for nosebleeds or raven droppings for toothaches. The variety of materials used for healing in medieval Europe is both surprising and intriguing, reflecting the creativity and resourcefulness of the healers of the time.

Mercury(that today we know is harmful for the human body) was also used in the preparation of some medicines, as well as gold or some dust gathered from Egyptian mummies. These medicines were very expensive and so only available to the very rich people, highlighting the stark inequality in healthcare access in medieval Europe.

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

Beer in the Middle Ages

|

| This is the interior of an old inn in Bucharest, Romania. It is called "Caru cu bere" which may translate as "The Beer Wagon" Photo by Baloo69 on Wikimedia Commons may translate as |

Back in the day, they even made beer soup for the entire family; parents, grandparents, and kids were fed with beer soup.

Beer Soup Medieval Recipe (When beer was served for breakfast and beer bellies were well respected) This is an article I wrote last summer for Hubpages. It is a short history of beer mainly with the purpose of introducing an old beer soup recipe.

Today I want to speak about beer as a drink in the Middle Ages.

Now, we may think that centuries ago, the best drink for most people was water. And this is partially true. But we do not know that a better drink for our ancestors was beer. And it was quite common among people of all conditions and ages.

One reason they consumed beer was that the water was often impure, posing a health hazard. In this regard, beer was far healthier. The fermentation process of the grains destroys most of the harmful bacteria and other germs that may contaminate the water, so beer was a far more hygienic drink.

Beer was brewed by everyone. The earliest people we know today that they made this drink were Egyptians, some 2000 years B.C. It is said that Greeks and Romans liked wine, though they, too, knew how to make beer.

In the Middle Ages, beer was made at home by housewives, sold at taverns to customers, and in large commercial enterprises for mass consumption. It was so popular that it became the drink of the “common man,” with the largest consumption in German Countries, the Low Countries, and England. It was even a method of payment for workers.

Beer also had its rules and regulations in cities and monasteries, where monks got beer at strict ratios. In London, they had to limit how much water you could draw from a well or spring. (Because they would dry out the wells). In fact, some historians have said that, for the countries mentioned above, there was one brewery for every one hundred people. In this condition, it is no wonder that the municipality of London found them dangerous for the public water supplies.

Beer was not the only drink, though. They also made wine, especially in Greece, Italy, Spain, France, and other eastern and central European countries. With all these drinks, medieval people did not give up on water. But this may be my next subject.

Sunday, June 5, 2011

Preserving food for later use or transportation

|

| Sea salt harvest - France Rolf Süssbrich -own work |

Sea salt was obtained by flooding specially constructed fields near a sea. The water evaporated, and salt (with grit and other impurities) was at the bottom. This salt was cheap to obtain and cheap to sell and could be produced at large scales.

More pure salt was obtained from natural springs that run through salt deposits in the ground. A series of pipes was set to capture the water of such springs. Then, the water was boiled in huge kettles until evaporation, leaving a better salt behind. The third way to get salt was by digging it in salt mines.

Salt was used to preserve meats and fish, cheese, and butter.

Fruits were dehydrated on large wooden surfaces, often placed outside, under direct sun, and indoors, in a room with opened windows to allow air to circulate. They dried grapes, apricots, apples, dates, figs, pears, peaches, and many other fruits. Some fruits were coated with sugar and dried again. Some vegetables, like beans, peas, and lentils, were harvested already dried; others, especially the root vegetables, and potatoes, were stored in a cool, dry place and sometimes buried in sand in a sheltered place. They also dried all the herbs used in cooking (or healing practices).

They also used brine (a mixture of salt and water) to preserve the texture of meat. The meat or fish was sunken in brine and left until consumption. The same mixture was used to preserve the cheese. Many vegetables were also pickled in the same way.

A brine mixture with wine, vinegar, spices, and seeds was most often used for pickling.

The wine was also combined with sugar and turned into syrup for preserving fruits.

The oil preservation method was widely used for packing olives. Animal fat was used to preserve cooked meats. Fried or roasted meat was immersed in liquid animal fat and preserved until ready for a meal. Sometimes, instead of fat, they used gelatin obtained by boiling hooves and feet from animals.

People mainly preserved food for later consumption. Winter was especially hard since no vegetable could grow. The fruits and vegetable were picked and dried at the end of the season. The roots were collected at maturity and sored in dark, cool and dry places. Meats were preserved mainly at the end of fall, when most cattle were slaughter. Pigs were sacrificed even later when the people exhausted the fodder.

People also preserved food to prevent it from spoiling during transportation. As roads developed, more and more goods were traded between different parts of a country or between continents. Spices and exotic fruits came to Europe, and later, coffee and tea were introduced.

Friday, June 3, 2011

Country side diet in the Middle Ages (aprox. 1000 to 1300)

|

| Medieval farmers, paying the "Urbar." |

Today, it is very difficult to reconstruct the life of a peasant in the Middle Ages. If there are plenty of records for the upper classes, historians have to dig deep for information about the serfs. The documents that they can find are tax records, donations, wills, household inventories, or funeral banquets. One of these documents shows us that in 1268, in the domain of Beaumont-le-Roger, in France, a couple would receive one large and two smaller breads, 2.5 a gallon of wine, 250 gr. of meat or eggs, and a bushel of peas. And this pay was considered high.

These serfs were populating the rural areas, and they accounted for the majority of a country's (or kingdom's) population. Around the house, they were given a small piece of land, like a regular backyard today, where they were allowed to do whatever they wished. Almost all families were growing some kind of animals and birds and cultivating a small garden. They usually had pigs, goats, sheep, and a few chickens or geese. For everything they grew or raised, they had to pay taxes to the landlord in the form of produce they got: eggs from birds, meat, wool, and milk from animals.

Their diet was very dull compared to modern eating habits. The base of a daily meal was the bread. Often made by secondary cereals like barley, rye, spelt, or a mixture of grain. Today, we would consider this type of bread healthy compared with the withe bread, but long ago, it wasn’t as easy to process cereals (and deplete them of all the good nutrients). The bread of peasants was very dark in color. The lighter the color of bread, the higher the social status.

The other product in their daily diet was wine. Grapes are easy to grow in good soil, and the wine-making process is an old discovery. In the Middle Ages, having a winery was so common that everybody knew how to make wine. Remember, peasants got wine in exchange for their labor. If they owned a small piece of land, they would cultivate some grapes, too. This habit has survived to this day in Europe, and we can still find many family farms that cultivate grapes to make wine. So, wine was popular and was consumed by everybody in the family, like beer.

Meat was another important part of the Middle Ages diet. People got the meat either as pay for work or from their own small backyard. Sometimes, they hunted small game, but hunting big game was mostly a privilege of the nobles. The meat was consumed mostly fresh and sometimes was salted and smoked to be preserved over the winter. Again, the ratio of meat was very small, and most days, it was not even part of the meal. Along with meat, as a product of the sustainable small economy, cheese, milk, and eggs were used.

Vegetables were largely consumed. The little backyard of a cottage that belonged to a peasant had a garden where women, children, and elderly folks who lived in the house would cultivate legumes, greens, and vegetables such as cabbage, onion, garlic, turnips, a variety of beans and peas, leeks, spinach, squash, etc. From the wild, they would complement with mushrooms, asparagus, watercress, and a few aromatic herbs like basil, fennel, marjoram, or thyme.

These folks in the Middle Ages were completely dependent on the weather for their survival. If the year was bad (too dry or too wet) and the cereal crop was compromised, then they could face famine. Between 1000 and 1300, four major food crises affected Europe (1005-6, 1032-33, 1195-97, 1224-26). However, the human species survived to this day and writes stories like this one on the Internet!

Thursday, June 2, 2011

The art of eating together - conviviality

Conviviality is seen as a distinguishing feature between animals and humans. Since prehistoric times, people have gathered to find food, cook food, and eat together. Not only is this conviviality a sign of civilization, but it is also a sign of social status. The richer the meal, the higher the class.

People have organized parties since the Neolithic revolution, when societies started to settle and aggregate around fertile lands, forming communities and building cities. These parties, called banquets, were very often a privilege of the ruling classes. Until the second half of the 20th century, food was consumed for survival worldwide. And it is still a problem these days in some parts of the world. So, only the rich could afford to throw a party. Some foods were considered a sign of luxury and abundance.

For centuries, the banquets of the rich served multiple purposes: to show off, to make friends, to indebt someone, or to pay respect. And not everybody invited to the party had the same treatment as today. There was discrimination, as we would put it in modern times. The guests were separated by social status: there were sovereigns and vassals and servants and employees. There were even gods invited to come, and they were set at separate tables (later, when the party was over and the guests were gone, the host would eat the meat reserved for those gods).

The hierarchy and power position among the participants at a banquets was shown through the place everyone sat at the table. The higher the position in society, the better place at the banquet table and also the better the food.

A very successful or important party was often recorded in writing to be remembered by the posterity. That’s how we know now when it took place, where, who came to the banquets, what kind of food was served and in what quantities (because the bigger the quantity, the richer the host), and what other events took place, if any.

As time passed, conviviality evolved from a simple act of gathering to an art form to be learned and displayed.

|

| wikimedia commons Giulio Romano, Amore e Psiche, Palazzo Te a Mantova. |

People have organized parties since the Neolithic revolution, when societies started to settle and aggregate around fertile lands, forming communities and building cities. These parties, called banquets, were very often a privilege of the ruling classes. Until the second half of the 20th century, food was consumed for survival worldwide. And it is still a problem these days in some parts of the world. So, only the rich could afford to throw a party. Some foods were considered a sign of luxury and abundance.

For centuries, the banquets of the rich served multiple purposes: to show off, to make friends, to indebt someone, or to pay respect. And not everybody invited to the party had the same treatment as today. There was discrimination, as we would put it in modern times. The guests were separated by social status: there were sovereigns and vassals and servants and employees. There were even gods invited to come, and they were set at separate tables (later, when the party was over and the guests were gone, the host would eat the meat reserved for those gods).

The hierarchy and power position among the participants at a banquets was shown through the place everyone sat at the table. The higher the position in society, the better place at the banquet table and also the better the food.

A very successful or important party was often recorded in writing to be remembered by the posterity. That’s how we know now when it took place, where, who came to the banquets, what kind of food was served and in what quantities (because the bigger the quantity, the richer the host), and what other events took place, if any.

As time passed, conviviality evolved from a simple act of gathering to an art form to be learned and displayed.

Wednesday, June 1, 2011

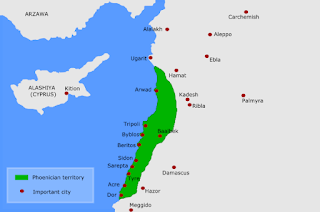

Phoenicians and their foods

|

| Phoenicia. Kordas, based on Alvaro's work. |

Take the Phoenicians, for example. They ate cereals, especially wheat and barley, often imported from Egypt. They made porridges, breads, and flat cakes that grew in popularity, crossed borders, and survived for centuries. They also had vegetable gardens where they would grow peas, lentils, chickpeas, beans, and a variety of fruits.

The most popular fruits were pomegranates and figs. The pomegranate fruit was considered a fertility fruit due to its abundance of seed. Figs were considered delicacies and exported to other neighbors (Egyptians). Other fruits they cultivated were dates, apples, quinces, almonds, limes, and grapes.

Grapes were also used to make wine, just as today. The wine-making process was well developed, and there is evidence that wine was “running like water” in a city called Ullaza, meaning that they had a great production of wine. (1) Wine was widely used in religious rituals.

Oils were used in cooking, and it is said that their extraction began in the third millennium B.C.E.

Phoenicians also ate meats (sheep, cattle, rabbits, chicken, doves, and game), milk (a highly appreciated product) and honey (used in cakes and imported from Judah and Israel), fish, salt.

The essential diet in Carthage and the Punic Empire, especially its western territories (Sardinia, Sicily, and Spain), was a dish called puls - a porridge made from mixed cereals. It was embellished with cheese, honey, and eggs.

Here is a simple recipe from Cato, a Roman who fought in the Punic War and wrote a book called De Agri Cultura:

“Add a pound of flour to water and boil it well. Pour it into a clean tab, adding three pounds of fresh cheese, half a pound of honey, and an egg. Stir well and cook in a new pot”.

1. Food, a culinary history Ed. by Jean-Louis Flandrin and Massimo Montari, 1999, p.57

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)